The Gathering Storm

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Moria had christened Afeez’s taxi “Ajagbe,” a name plucked from a word she had heard as a child “Ajagbe-mo-keferi.” A fitting moniker, she thought, for a car that rattled and groaned its way through Ibadan, yet, miraculously, never failed to deliver..

She had initially questioned her sanity in choosing this clattering chariot for her travels, but pragmatism had won. A last-minute phone call, received somewhere along the Lagos-Ibadan Expressway as Denrele drove her to Ibadan, had shattered her plans: her pre-arranged Ibadan transport had become a mangled wreck from an accident. Ajagbe and the unflappable Afeez had become her unexpected saviours.

The Moria who now sat in Ajagbe’s backseat was much different from the elegant figure Afeez had collected from Molete the previous day. Gone was the polished sophistication, replaced by a simple t-shirt, worn denim, and a discreet scarf. Only her signature eyeglasses and the lingering, unmistakable scent of her perfume remained unchanged. A wise voice, perhaps her own, perhaps Mulika’s, had whispered a crucial truth: leave the Boston persona behind. Blend, adapt, survive, and she had listened.

Afeez found himself strangely invested. More than a taxi driver, he was now a protector, a guide. Moria’s mission, however, remained shrouded in mystery. What drove her? What reward lay at the end of this dangerous path? Everyone knew the Agbekoya, their name a byword for courage in Ibadan’s folklore. Why was she so determined to understand their story? He had so many questions but lacked the boldness to seek answers from Moria as they started their trip for the day.

The Beere-Orita-Aperin Road stretches from Beere with its multiple intersections, descending sharply towards Oranyan, where it crosses the Kudeti River. As it starts its ascent at Oke-Labo, it crosses the Oluyoro River and then winds up through Elekuro to Orita-Aperin. It is on this arterial route that the Baale chose to build his house, not far from Wesley College, a renowned teachers’ training institution in Western Nigeria that produced prominent figures like Obafemi Awolowo, the first premier of the region.

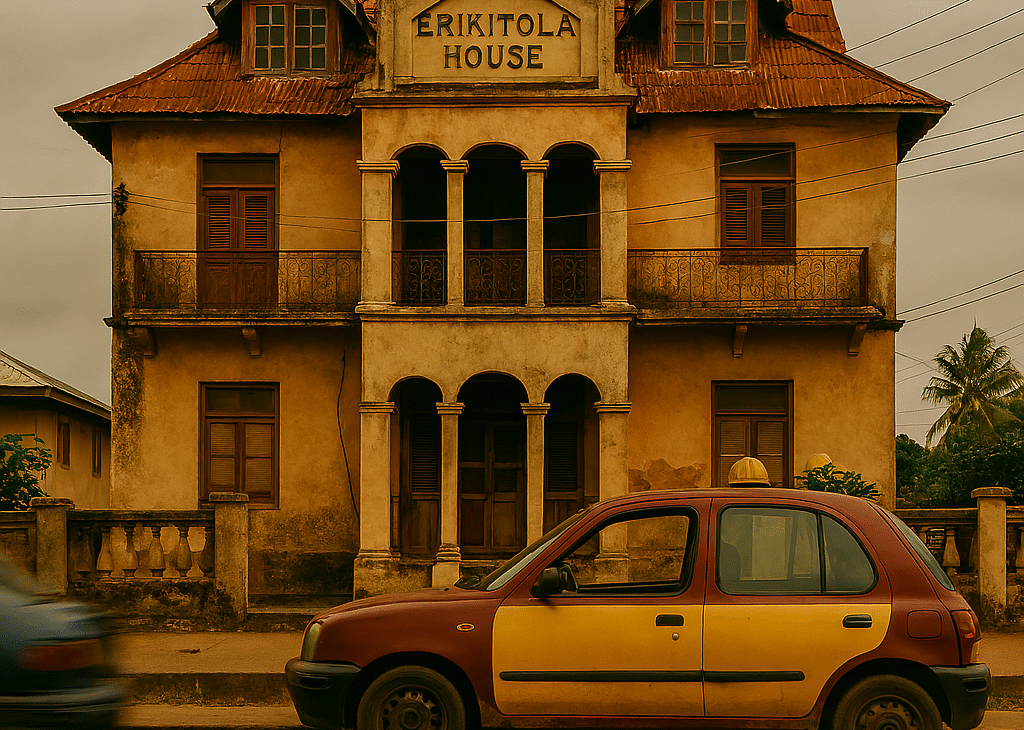

Facing this winding road at Oke-Labo stands his impressive house, called Erikitola House. This two-and-a-half-story structure is influenced by British architecture. It stands out among the local houses due to its additional half-floor that serves as a third floor, providing an unobstructed view of the surrounding landscape. From here, one can see as far as Beere, Oja-Oba, and Oja-Igbo. Some visitors to the house have claimed that it offers a better view of Ibadan than that from the historical Bower’s Tower in Oke Are known for its 360-degree panorama of Ibadan.

Easily visible from the road is the large wooden signboard with a white background, prominently hanging from the metal balustrade that adorns the first floor. The inscription on the signboard, now faint but still legible, reads:

Samuel Tayo Bakare

Erikitola

S4/285 Oke-Labo, Ibadan

On one side of the board is the drawing of an elephant, while on the other is that of a tree in full bloom. Chipped on its edges and now hanging on a loose wire tied to the balustrade, it had all the telltale signs of its age.

Like many of Ibadan’s prosperous men of his time, the Baale had maintained a city residence, a haven of comfort far surpassing his village dwelling. It was to this house, now hemmed in by the skeletal frame of an unfinished building, partly blocking it from its former unobstructed view of the road, that Afeez brought Moria and Mulika, their journey leading them towards Ijebu-Igbo. Oladosu, a grandson of the Baale, was waiting by the side of the road to receive them.

Mulika’s tales of the Agbekoya’ assault on the house, riddling it with bullet holes, echoed in Moria’s ears as they stepped onto the balcony. Her eyes scanned the walls, searching for the scars of that violent day, but found nothing. A sigh escaped her lips. Time, she reasoned, had likely erased the evidence.

Inside, the house echoed with emptiness. No children’s laughter, no voices, not even the bleating of a goat disturbed the stillness. Moria felt the weight of absence; the silence spoke to her of lives lived and lost. The Baale was long gone, claimed by death a mere seven years after the Agbekoya uprising. Some whispered that the trauma of the conflict – his burnt farms, the forced exile, the siege of his own home – had hastened his demise. His wives, Adejoke, Faderera, and Olaoti, had followed him into the silence, one by one, with Olaoti being the last.

Before them, a wooden staircase ascended, its steps worn smooth by countless feet. The handrails, adorned with intricate carvings, bore faded patches of their original green paint. Each worn step a remembrance of lives that had passed. At the landing, Oladosu had arranged seating on the first-floor veranda.

From this vantage point, Moria saw Afeez and his faithful Ajagbe parked below, and the ceaseless flow of traffic on Elekuro Road. The surrounding landscape was a sorry sight of decay, crumbling buildings hinting at a forgotten era. It was hard to imagine that this had once been a neighbourhood of influential men, their legacy now abandoned, their descendants scattered all over the world in search of opportunity.

Their initial phone call had set the stage. Moria’s goal—to understand the Agbekoya story—had resonated with Oladosu, a firsthand witness to the Baale’s involvement. His narrative flowed smoothly, polished from years of retelling. He explained Tayo was a pillar of the community, holding many roles: cocoa farmer, Baale of Olorunda Village, customary court judge in Akanran, and a member of the Ibadan City Council. As Oladosu spoke, Moria’s fingers flew across her notebook, capturing his words. She interrupted only occasionally for clarification, mostly allowing him to freely share his knowledge of the Baale’s role in the Agbekoya Uprising.

The story, as told by Oladosu, had unfolded in a flood of detail. Moria had recorded every word, but the story was not yet hers. It was only later, in the warm, dim light of the Premier Hotel’s bar, with the rich tones of Lady Essien Igbokwe filling the air, that she could finally process all she had heard. She opened her notebook and switched on her Palm Pilot, ready to reshape the raw facts into her own narrative and wrote:

It was evening when the Baale finally found a moment of peace on his modest home’s balcony, relaxing after a busy day. He was resting on the wooden rocking chair, and from where he sat, he could hear the voice of Akanno, his junior brother, talking to someone in the next building while his eyes were darting between watching the traffic on the road and his grandchildren playing “Okoto” nearby.

The news jingle, the short musical piece signalling the start of the news broadcast, came on air on the radio. He mused as he pondered on the true meanings of the bata drum beat in the jingle. With many interesting interpretations, he liked the one that interpreted the beats as “T’Olubadan ba ku, tani o’joye?”

He quietens his grandchildren from their noisy play so that he can listen to the news rendered in the English Language. The Baale’s brow furrowed on hearing the government’s announcement of a significant increase in taxes, a move that he immediately knew would undoubtedly hit the rural population hardest. As a cocoa farmer in the Akanran area, he had witnessed firsthand the struggles of his people, their resilience in the face of adversity, and their unwavering connection to the earth. The new taxes would be a catalyst for unrest.

In Ibadan, the very air hums with the memory of past prosperity. The city, built on the wealth of cocoa, showcases the region’s dominance in the trade. The towering Cocoa House, the tallest building in West Africa, stands as a silent monument to this.

Yet, that wealth is now feeling like a distant dream. The Nigeria Cocoa Marketing Board (NCMB) derisively nicknamed “Ensin embi”—”You are killing it and still asking”—by disgruntled farmers, controls the prices, dictating their livelihoods. But volatile international markets and shifting government policies have sent cocoa prices plummeting, and many farmers are now barely surviving.

The hardship isn’t limited to cocoa. Traders in other commodities are also feeling the pinch. Asake Olusoga, a palm oil trader, is a perfect example. She once made a decent living, buying palm oil from distant villages and selling it at Ibadan’s bustling Oja-Oba market. Her clients came from all over, Lagos and Ekiti, and she even shipped oil from Dugbe Terminus to customers as far away as Zaria by rail.

Not anymore. Her customers are struggling, and so is she. The cost of transporting the palm oil from the farms to the city has exploded, leaving her with barely any profit. Her customer base has shrunk dramatically. The income she makes now barely supplements the cost of her son, Tomoye’s education, even though his brilliance has secured him numerous scholarships. Everyone, it seems, is just trying to stay afloat.

Kolapo, on the other hand, is a product of a different era. He is one of the few who benefited from the produce licenses that the late premier, Samuel Ladoke Akintola, handed out to his supporters. Now, with Adebayo’s new government, he faces a future with less access to the trading opportunities he once took for granted. He has to act, and he isn’t going to wait to find out if his fears are true. If A.M.A. says it, he believes it, and A.M.A. had not minced words when he told him about Adebayo’s plans to raise taxes.

Kolapo remembers Tafa and his antics with the Maiyegun League – a fiery group from the days when the government tried to cut down cocoa trees to fight the swollen-shoot disease. It’s time to get him involved.

Two days before the Governor’s announcement, Kolapo invites Tafa to his depot, where cocoa bags are graded and stored before being transported to Apapa for export. Over bottles of Fanta, a plate of Cabin biscuits, and some fresh kola nuts, he tells Tafa about the impending tax increases and the immense profits the Nigeria Cocoa Marketing Board (NCMB) is making from cocoa sales, all while the farmers struggle.

“Ma ma je keni keni tan e je,” Kolapo says, his voice dripping with false concern. “Don’t let anyone deceive you. The cocoa business is lucrative, but not for farmers like you.” He whispers, “We must resist these new taxes. This government needs to understand that farmers cannot continue to be exploited.”

As Tafa leaves that day, he thanks Kolapo for the information. Kolapo hands him an envelope with money for transportation, assuring him that he can always count on his support. The words echo in Tafa’s mind, fuelling a growing sense of determination.

These new words mix with the memory of Adisa. Tafa can still see the worry on Adisa’s face – a hardworking farmer forced to leave his village for the cruel uncertainty of unemployment in Ibadan. Tafa thinks of his own struggles; despite his backbreaking labour, he and his family live from hand to mouth, unable to afford a decent home for his wife, Suweba, and their children. He hears Suweba’s complaints about the maternity ward, and he remembers the roads, riddled with potholes that go unrepaired. Just the other day, his Bolekaja had narrowly avoided a head-on collision with a Peugeot pickup that swerved to miss a crater in the road.

He thinks of the cracks in his own mud house that he can’t afford to fix, and the gall of government officials living opulent lifestyles, now emboldened to increase taxes and worsen the plight of farmers. A Yoruba saying comes to his mind: “When you chase a goat to a wall, the goat will turn back and fight.”

If he has ever been determined to do anything, it is now. He knows the time for inaction has passed. It is time for the farmers to stand up and demand justice.

The alarm clock’s shriek sliced through the quiet. The Baale, feeling as though he hadn’t slept at all, reached out and silenced the insistent noise. A weight settled in his chest as he left the quiet of his home and stepped out into the pre-dawn chill, making his way to the local bus park.

As the bus arrived in Akanran, The Baale felt a knot of unease tighten in his stomach. The usual bustle of sellers setting up their stalls was absent. Alighting from the Bolekaja, he heard a distant commotion, a rising tide of sound that drew him forward. He knew this community. He knew that sound. It was the sound of farmers finally pushed to their limit. He was right. As he approached the town square, the voices grew louder, punctuated by a defiant chant: “A ko ni gba iyen!”[1]

The town square pulsed with a sombre tension. A crowd of farmers, their faces wild with determination, had gathered. Their leader, Mustafa, a fiery young man well-known to the Baale, stood at the centre, his voice booming with indignation.

“The government has pushed us too far!” he roared. “They think we are mere pawns to be manipulated and exploited. But we will not stand for it! We will fight for our rights, for our land, for our dignity!”

The crowd erupted, their cheers echoing through the town. The Baale listened, his heart swelling with a mixture of pride and fear. He had always known the people of Akanran were resilient and courageous, but today, he saw something new: unity, unwavering resolve, a readiness to fight for their future.

He recognised others in the crowd: Tafa Adeoye and Akekaaka, both familiar faces to the Baale. Tafa, quiet and thoughtful, was cut from a different cloth from the boisterous Akekaaka, who was standing firmly behind Mustafa, fuelling his passion. The Baale instinctively knew that Tafa, despite his quiet demeanour, was the true mastermind behind the uprising.

He also spotted Ajireni among those seated. Knowing Ajireni’s deep-seated hatred for him, the Baale decided against joining the gathering. Since the judgment he gave on Mulika’s case, the Baale had learned to avoid Ajireni. Their few encounters had made it clear: if Ajireni had his way, the Baale would be a dead man.

Without disturbing the scene in the town square, he quietly slipped away towards his village house in Olorunda, nearby. He knew what he had to do. He needed to speak with Tafa.

A gentle tap on her shoulder jolted her from the depths of her thoughts.

“Ma’am, we’re closing. Would you like to continue in your room?”

The music had stopped, the last echoes of the day fading into silence. She looked at her watch: 1:15 AM. The hours had vanished. For so long, she had been lost in a world of her own making, the words flowing effortlessly from her mind.

Her eyes fell on the notes from her meeting with Oladosu – so much still to write. A yawn broke free, heavy and unrestrained, betraying the fatigue she had stubbornly ignored. It was time to retreat to her presidential suite. Only then did she remember Mulika, likely fast asleep by now. The poor woman had been drained when they returned earlier, guided by Afeez and “Ajagbe,” after a day steeped in history: the solemn ground at Lalupon where Fajuyi and Ironsi were found, the sweeping views from Bower’s Tower, and the grandeur of Adebisi Mansion in Idikan.

Of all the stories, Adebisi’s had gripped her most – his bold pact with the colonial office to shoulder Ibadan’s tax burden, a man wrestling with the similar tax palaver that had now given rise to an uprising, shaping the city’s fate.

She had promised Mulika she’d only be gone a few minutes. But minutes had stretched into hours. With a quiet thank-you to the bartender, she gathered her things and took the elevator up. She didn’t stop by Mulika’s room. Instead, she slipped into her own, surrendering to the embrace of the bed. The story that had brought her here could wait. She would continue it tomorrow.

Amina Yusuf

@Bimbo, may I beg you to provide more of the Sampler? This story has left a taste in my mouth wanting more. Otherwise where and when can I get the book to buy?

Ohanugo Ernest

Well done Bimbo. I am.looking forward to the main book. You are an amazing story teller. You have shown another side of you brilliance by this work. I am proud of you 👏

bimbo

This means so much, thank you Bishop

Gbenga Adewale

Egbon, nice one. well done. Great story but I was unable to open the link to read the rest of the book

Eno Bassey

Lovely story but what happened to Moria?

Segun Toluwade

Lovely writing. Interesting concept and engaging story plus nostalgia. One comment though: I’m not familiar with how writers put stories together, but I imagine you have a panoramic view of how the whole story will ultimately come together? Or there’ll be a rearrangement of chapters and subplots etc further down the line as you get these feedbacks…

Welldone!

——————————

All the best!

bimbo

Thank you very much for taking time to give your feedback, I do not take thus lightly.

Yes, the chapters are arranged differently in the book, different from how I had shared them.

A little secret is to follow thee indicator at the end of each chapter, ajust above where I put my name as author.

Again, thanks a ton.

William Kareem

So far, your story had been gripping, informative and illuminating. Your descriptions bring back exciting memories of ‘area wa’ in Ibadan City. Semper Optimum!

bimbo

Ore, thanks for your encouraging words. Well appreciated

Y Oladeji

Bimbo Bakare’s new novel is a brilliant tapestry of civil conflict, socioeconomic dichotomy and the cruel “fragility and fickleness of destiny”.

This work, in my limited knowledge, is a pioneering work of story telling of a civil conflict in which the hidden connections between these events are justly revealed .

Every character has a unique role in revealing the nature of our society.

The preponderance of good over evil , and charity over self-centeredness is evident .

As I dig deep into these excerpts, I am beginning to understand while the people in diaspora are often conflicted in their perspective of our motherland .

Moria’s quest to revisit the past and her methodology of reconnecting is refreshingly simple but powerful.

I also notice the ever presence of opportunists even in the villages , where we see greed , impunity and oppression of few privileged individuals.

The rise of just rebellion against callous policies by ordinary men of Tafa’s extraction is a reminder that we have always been republican minded people.

People of good will do exist, and circumstances have ways of fishing them out.

Bakare’ s skill in writing this story makes me wondering and eager to know what inspired him to embark on this literary exploit .

I patiently await the complete story and the exciting dialogue that follows.