Big problems start small

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

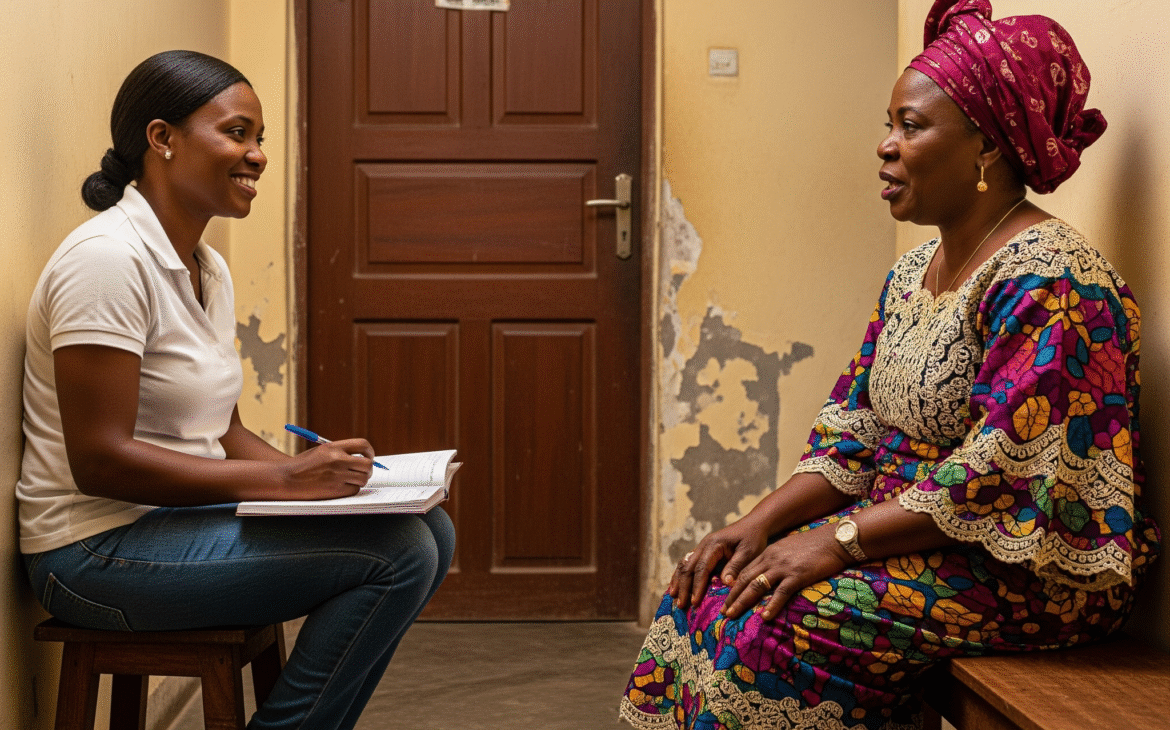

From the moment she was welcomed into Mulika’s presence, she remembered how, after a few brief exchanges of pleasantries, the conversation had been dominated by Mulika’s storytelling. Moria had done her best to capture every detail, and only now did she have the time to weave it all into a narrative that fit seamlessly with the story so far. She began to write:

The seeds of revolt had been sown by the gods themselves. It all began on a rainy morning when the relentless downpour, a steady drumbeat against the thatched roof, seemed to echo the mournful howl of the wind. Tafa Adeoye stirred, his eyelids heavy with sleep, as the cold crept through the walls of his mud house. The wind, like a mischievous spirit, whistled through the cracks, carrying with it the scent of damp earth and decaying leaves. A knock at the door jolted him awake. It was not yet daybreak, and even if it were, Tafa was not one to rise this early, especially since the cocoa harvest season had just ended. He reached for a matchstick and lit the Atupa[1] which casts a faint glow around the room.

Suweba, his pregnant wife, shifted beside him. “Who could that be at this hour?” she murmured, her voice barely audible. Grudgingly, Tafa crawled out of bed and made his way to the door. He swung it open, the cold air rushing in. Adisa, one of the village farmers, stood on the doorstep. His face was filled with sadness, and Tafa could see that he was fighting back tears.

“What is it, Adisa?” Tafa asked, his voice filled with concern. “Is something wrong?”

Adisa hesitated, his eyes darting nervously. “I came to tell you about the Chief,” he finally said. “He has asked me to leave his land and to do so within the week. I still have cocoyam that I have not harvested, and at the start of this year’s rains, I had planted cassava all over the one on the right side of Akinola, not far from the Oshun River. He is not compensating me for any of these.”

Tears welled up in Adisa’s eyes as he continued his lamentation. “Yes, the land is his but asking me to leave without adequate notice is just unfair. And you know what he did to Adeoba and his family; he is ruthless, and we all know no one is bold enough to ask him to desist, once his mind is made up.”

Tafa’s heart sank. While the news was overwhelming, it was not surprising. Adisa had been unable to pay the Isakole[2] to the Chief for a few years and had seen this coming for months now. The Chief’s underhanded tactics were nothing new, but this was different. Adisa was a hardworking man, and this land was his livelihood.

“What are you going to do?” Tafa asked.

Adisa shook his head. “I don’t know,” he replied. “I’m thinking of going to Ibadan. There might be work there.”

Tafa listened in silence, his mind racing. He knew that Adisa was desperate, and he couldn’t bear to see him leave the village. But what could he do? Adisa hadn’t come to him just because he needed a sympathetic ear, but obviously because he needed financial help, but his pride wouldn’t allow him to ask. Tafa understood; they had been friends for so long that he could interpret the lines of worry on Adisa’s face as that.

Adisa was a true friend. He recalled how Adisa had stood by him when he had the unfortunate incident of the snake bite on his cocoa farm. If not for Adisa, who had quickly applied local herbs and carried him on his back all the way from the farm to the village, he would have been a dead man. He owed Adisa his life.

Suweba is having a troubled pregnancy. The maternity ward at the Akanran Health Centre was derelict, with no drugs and the nursing team treating patients as if they were rendering a favour rather than the services they were being paid to render. Just the previous day, Suweba had come home complaining about the eerie glow of the peeling paint in the maternity ward, the stale scent of disinfectant and antiseptic, and the heat due to the lack of electricity to power the fans. At her last visit, she had been called into the small and cramped examination room, with faded curtains, and asked to lie on a worn, vinyl mattress. Her back ached as if she had lain there for hours before the midwife eventually got to examine her by running her hands all over her stomach, trying to feel the kick of the unborn baby, all while the midwife was distracted.

Suweba’s fear was palpable. Tafa remembered the look in her eyes as she pleaded with him to make arrangements for her to go to Adeoyo Maternity Hospital in Ibadan when her labour begins. “I don’t want to die during childbirth,” she had said, her worry clear in her expression. Since that discussion, all Adisa’s savings were being directed towards taking care of Suweba, and he is low on finances for anything else.

All these thoughts raced through Tafa’s mind, but despite them, he felt Adisa needed help now. He asked his visitor to wait as he took the Atupa and headed back into his room. Suweba, still asleep, asked, “Who is there? Hope all is well?” She turned on the bed facing the wall without waiting for a response and continued with her sleep.

Tafa took another look at his wife, the mother of his children, and the bed on which she slept, then around the mud-plastered room in which they slept. A teardrop formed in his eyes. He was sure they deserved better. They were not lazy people. Year in and year out, he had been cultivating the little Cocoa farm that he inherited from his father, but the income had not been enough to cater to the needs of his growing family. He was almost lost in his self-pity when the sound of a little movement in the room he had left brought him back to the present.

He reached for one of the dresses that he had hanging on the nail on the wall, checked the pocket, and took out one Nigerian pound. That was what he could afford, and he hoped it could provide some succour to Adisa as he faced an uncertain future. Back to where he had left Adisa, he handed him the note, explaining to him to accept it as his widow’s mite.

“Isn’t this too much?” Adisa said while receiving the money. “I am very grateful. This will help a lot with our transportation and the first few days of our arrival in Ibadan.”

“Don’t mention,” Tafa answered. “I wish we had more. I could have given to you, but please try to make use of that as you need.”

With Adisa out of the house, Tafa turned the wooden bolt back at the door and locked it. He opened the door of the next room to check on his children and then went back to meet Suweba on the bed, putting off the Atupa.

As he lay on the bed, Tafa started ruminating on his life journey. Tafa, a cocoa farmer with a small plot of land, had always managed to make ends meet. He supplemented his cocoa crop with seasonal plantings of cocoyam and corn, ensuring a steady supply of food for his family and a little surplus to sell at the market. However, as the years passed, the challenges of farming grew more daunting.

The recent announcement of new taxes on farmers was the final straw. An otherwise gentle soul, he was filled with a quiet anger. He understood the government’s need for revenue, but he felt that the new policies were inconsiderate and would only exacerbate the hardships faced by farmers like him.

While pondering the implications of the new taxes, Tafa made a decision. He knew he was not the only one struggling. He would have to speak out, to let the government know that their policies were hurting the people they were supposed to be serving.

Sleep finally claimed Tafa, but it was a restless embrace. A premonition, perhaps, of the tumultuous days to come. His peaceful slumber, once a nightly sanctuary, was now tainted with an unsettling unease. He couldn’t have known it then, of course, but his decision to speak his mind would shatter the quiet rhythm of his life as a farmer. His name would soon be plastered across the front pages of the Daily Sketch, the Tribune, and every major newspaper in the land, including the revered Daily Times. Even in the distant corridors of power at Dodan Barracks, in the bustling metropolis of Lagos, whispers of Tafa would echo through the halls. His story would become a battleground for national discourse, to be debated for years to come.

If Tafa could have glimpsed the future, he would have slammed the door shut on Adisa. The quietude of his life and the simple rhythm of the seasons were all he had ever truly desired.

It was all that Moria could write before her parched throat made her ask Mulika for water. “Mulika,” she rasped, “could I please have some water?”

“Yes, of course,” Mulika replied, struggling to rise. “I apologise for not thinking of it.”

Moria saw the pain on Mulika’s face and suspected the early onset of arthritis, a common but often misdiagnosed ailment in this area. The thick scent of Robb and Mentholatum balms filled the air, reminding Moria of how her own grandmother struggled with pain management.

“Please don’t worry,” Moria said. “I’ll get it myself. Could you tell me where the water is?”

‘The Amu[3] is in the corner of the room, at the foot of the bed,’ Mulika replied.

Moria rose from the seat, glancing at her watch in surprise. Two hours had already passed. She couldn’t believe she had been sitting there for so long.” Moria had sat with rapt attention, typing as fast as she could on the Pilot, completely absorbed by Mulika’s stories. Mulika’s words tumbled out, a long-awaited release, poured out like a burst dam as the floodgates of her memories were unleashed. She recounted everything she had heard about Tafa Adeoye, the celebrated leader of the Agbekoya, and the circumstances that had thrust him into the leadership of the movement.

When she arrived, the joy of seeing Mulika face-to-face was overwhelming for both. Though they had spoken on the phone a few times, the sheer delight of seeing each other’s faces was undeniable. Looking about fifteen years older than Moria, Mulika had aged, of course; no longer the beautiful, radiant young girl Moria remembered.

During school breaks, Moria’s father would take them to visit Mulika in the village, explaining that they were cousins. Moria, not one for genealogy, never questioned their exact relationship. They played, an inseparable pair, developing a deep affection for each other. She would often follow Mulika to the stream to fetch water, both girls bathing in the cool water before returning home, their heads laden with heavy clay pots.

Though Moria had always known that fate had placed her and Mulika on separate paths, her warm welcome hadn’t driven home the reality of their divergent lives. It wasn’t until she stepped into Mulika’s room that the differences became painfully clear. The difference between Mulika’s living conditions and her own comfortable Massachusetts life was immense. Life, she was sure, had dealt her a far gentler hand. And here they were, years later, reunited by the very story that had changed their lives in different ways, a story Moria was only now beginning to grasp fully.

Not that she needed any conviction, but entering the room leaves Moria with no further doubt that Mulika is a woman of very little means. Next to the wall was her single bed with some of her clothes piled up on it and taking a good chunk of the space. The room had a wooden window, cracked in the middle with age, through which a ray of light streaks into the room, offering the only illumination during the day, except when the single light bulb hanging from the wooden ceiling is switched on.

Mulika’s wooden cupboard, about five feet tall with two padlocked doors, stood directly across from the bed. Two black clay pots, one larger than the other, sat on top. Moria recognised them; her own mother had used similar pots, one for stew and the other for soup. Old newspaper sheets, carefully placed to protect the wood from soot, lay beneath the pots. Moria didn’t open the cupboard, but she correctly assumed it held Mulika’s food. She knew this type of cupboard; her parents had one in their room when she was growing up.

She spotted the Amu in the corner of the room and scooped some water into the plastic cup provided. A wave of hesitation washed over her. Was it wise to drink this water? Her urban immune system might not be prepared for whatever pathogens could be lurking within. Should she ask Mulika to buy her bottled water? The thought lingered, but ultimately, her American pragmatism prevailed: “Better safe than sorry.” With that, she set the cup aside, abandoning the idea of drinking the water, and made her way back to the corridor where Mulika was waiting for her.

“Mulika,” she said, “please forgive me. I’m no longer used to drinking from the Amu. Let’s go out and have a meal instead.”

To her surprise, Mulika understood completely. She asked for a moment to get ready, excusing herself to dress up. As she waited, Moria couldn’t help but reflect on the capricious hand of fate – a cruel and unpredictable force that so often derails lives. She and Mulika had started their journeys with such similar hopes, and Mulika, with her academic brilliance, had been the one expected to thrive. Yet now, they found themselves holding vastly different hands, dealt by life’s unpredictable game. The outcomes were worlds apart, and Moria couldn’t shake the thought of how fragile and fickle destiny could be.

[1] Palm oil lamp

[2] Annual tribute for the rights to use the land

[3] Amu – Clay water pot, usually kept in a corner of the room to keep drinking water cold.

Laide Adenuga

This is nostalgic. It is as if I am in the same place with Moria and Mulika, vividly dewcriptive.

Thank you for getting me interedted in the great art of storytelling

Mama Popo

Each morning, its becoming a routine for me to quickly log into your website and check if another update of the Moria story has been done.

My close friends here in Zambia are getting to hear the story from me, I am jelous of sharing the source with them.

Lola Bucknor

Bimbo! I can say with certainty that you are called to be a storyteller, not an Accountant. You are good. Really good.

Blessing

I definitely need to take creative writing classes from you, sir.

bimbo

It is in your blood, it runs in the family. You just have to unearth it.

Ohanugo Ernest

Well done 👏 ✔️ 👍. It keeps getting better. I am definitely hooked on this book.

Fatima Mohammed

Nice ):