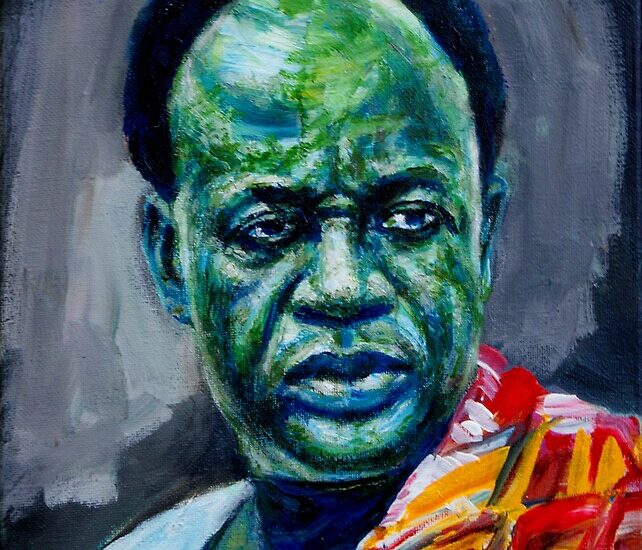

Osegayefo Must Die

From the moment Harold Wilson and Willy Spühler had this ill-fated conversation, Nkrumah was a sitting duck. Like Nero, fiddling while Rome burned, Nkrumah remained blissfully unaware of the impending doom. He had survived a few assassination attempts, which were like warning salvos that should have jolted him to caution. But those were for lesser beings, not for Nkrumah. Instead, he embraced a more flamboyant leadership style, adopting the title "Osegayefo," meaning "Leader of the People."